Related Topics

Most people are familiar with savings options available from banks—regular saving accounts, certificates of deposit and other time deposit accounts. Each of these is easy and convenient to use and there are times they are the perfect solution to saving money. Unfortunately, especially in today’s environment, any bank savings instrument has a weakness.

The return users earn on their deposits is minimal, almost to the point of being missing in action. Good for things like emergency funds but not so good to build assets for a future need—such as retirement. To build those assets it can be beneficial to include stocks and bonds in your retirement planning portfolio. People own stocks for capital appreciation (growth) as well as income (usually from company dividends).

Stock investments

When people own stocks they own a small piece of the company. One share of a company stock equals one ownership share of the company. Generally, owning a share of a large, well-established company is less risky than owning a share of a newer, smaller company. Why? The more well-established company is more stable, having weathered the inherent ups and downs of getting started. Larger, well-established companies often share part of their profits with stockholders in the form of dividends. Dividends provide the income component of stock ownership.

At the same time, those well-established companies don’t usually produce the investment growth (capital appreciation) that smaller companies, that don’t normally pay dividends, can provide. This regular cash flow may help to understand why larger companies usually produce investment returns that are more stable than smaller companies. Greater stability means lower risk. Less risk equates to less return – not always, but usually.

Investment risk in equities can be reduced in two primary ways – time and diversification. Over time, let’s say seven to ten years (plus), a stock’s ups and downs tend to level out. They’re still there but the years smooth out the ride. Diversification means owning stocks of several companies. Studies have shown that holding stocks from 15-20 (or so) large companies provides reasonable diversification and reduces overall portfolio risk.

Let’s think this through. It’s normally best, because of the economies of scale, to purchase stocks in what’s known as a round lot. A round lot equals 100 stocks. This means that owning the stocks of 20 companies means purchasing 2,000 total shares. Stock prices vary, of course, but if we assign an average price of $25 per share, the amount of money required to own all those shares is $50,000. That’s not an insignificant amount and may help to understand that, for many individuals, owning individual stocks does not make good financial sense until the person has at least two or three hundred thousand dollars that can be invested.

So, does that mean a person with more average assets cannot take advantage of stock market returns to build a retirement portfolio? Not at all. In fact, addressing that issue is one reason why mutual funds were developed.

Mutual funds

With a mutual fund an investor purchases shares of the fund and is immediately diversified. Mutual funds invest in a relatively large group of stocks and manages them for the benefit of shareholders. For example, if a person were to purchase one share of an S&P 500 (stock market) index fund, that person would benefit from owning the equivalent of stocks from all the companies represented by the index. If we apply the $25 share price previously used to a mutual fund share, the same $25 provides all the diversification needed to mitigate investment risk.

It’s a bit more complex than that, but the principle is accurate. As a result, many new investors are wise to invest in mutual funds – of which there are thousands from which to choose – as they build their portfolio. Time will remain an important factor but using mutual funds as an investment base nicely addresses the need for diversification. When someone puts money into an IRA or 401(k) plan they typically have the option to invest in shares of mutual funds. While greater returns are not guaranteed, investing in mutual fund shares is more likely to provide more growth than investing in stable value or guaranteed accounts.

Bond investments

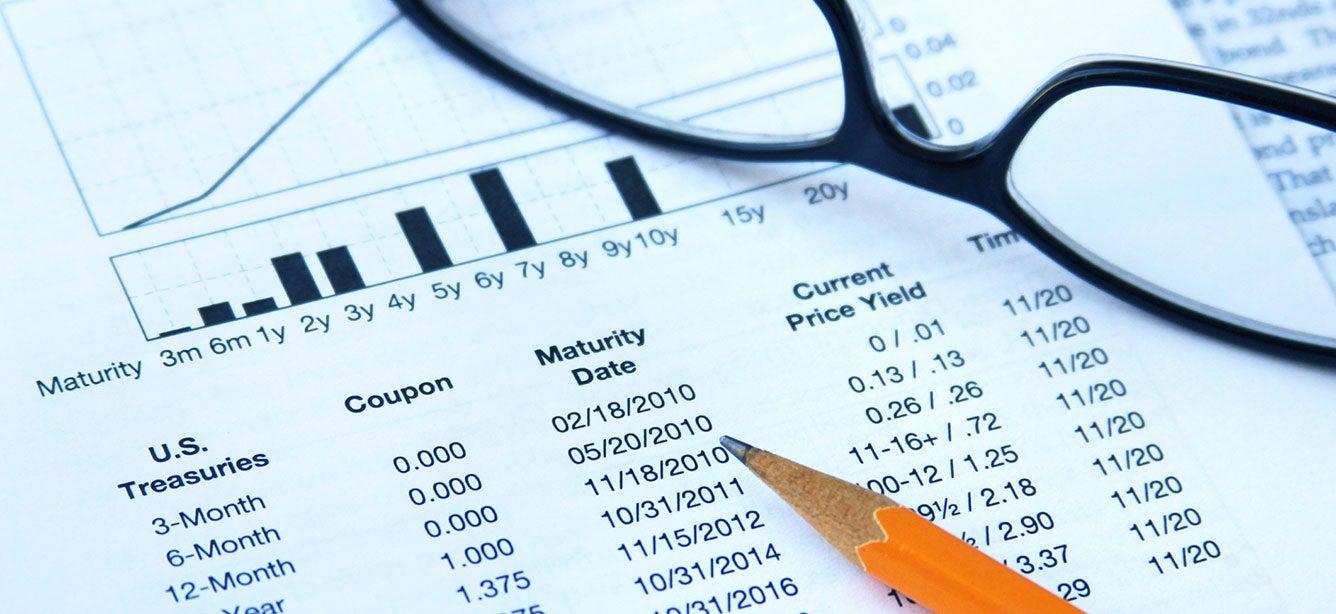

Bonds also provide opportunities for higher investment returns, but not nearly so much as do stocks. Instead, people purchase bonds (also called fixed income) for their income. Bonds come with what is called a coupon. Long ago, bonds actually had a coupon attached that bondholders would clip and take to a financial institution to receive a payment. When you own a bond you are lending money to the issuing organization, which could be a government or a company. To get people to lend the money, the issuer must pay interest. Interest payments are represented by an interest rate on the coupon.

As an example, a five percent coupon on a $1,000 bond will pay $50 a year. Bonds normally make interest payments twice a year, so a $50 annual payment will be made in two $25 increments. Bonds are issued for a set number of years; at which time a bond is said to mature. When the bond matures, perhaps in 20 or 30 years, the bondholder receives the bond’s face amount. The face amount is the original price at which the bond was issued - $1,000 for example. This means that high quality bonds bought when issued and held to maturity will return the full investment to the investor. Along the way, that investor would have received regular interest payments in addition to looking forward to getting back the original investment.

Generally, bonds require diversification in much the same way as stocks. It’s not quite as important with bonds, but reasonable diversification remains important. This points to the need for most investors to invest, not in individual bonds, but in bond mutual funds. As is true for stock funds, if an investor purchases one share of a bond fund, the investor will get immediate diversification among the bonds of many companies. Most IRA and 401(k) plans also offer bond funds as investment options.

New investors should understand another guideline. Normally, it’s important for an investment portfolio to balance ownership of stocks and bonds rather than owning all of one or the other. This is known as asset allocation and the most appropriate allocation for one person probably will be different than for another person. To help determine an appropriate asset allocation, it can be helpful to talk with a trusted investment advisor or financial planner. That said, a standard recommendation for a conservative, balanced portfolio might be to own 60% stocks and 40% bonds. That provides a combination of both investment options with a bias toward long-term growth. As mentioned, each individual’s best asset allocation will be different and should be carefully considered in the context of meeting personal goals.

Stock and bond portfolios in retirement

Sometimes people may decide to completely move away from stock and bond investments when they enter their retirement period. While this may seem reasonable as a way to reduce portfolio risk, it’s probably not the best idea. Why? Stocks, and to a lesser degree, bonds, can help mitigate the negative impact of inflation. Most people will be retired for two or more decades. During that timeframe inflation will continually erode purchasing power. This means, with historically average inflation of around three percent, after a little more than 20 years it will take twice as much money to support the same lifestyle as at the beginning of the retirement period. Groceries will cost twice as much. Medications will cost more. Fuel will cost more. Just about everything will be more costly. Bank deposit, while not subject to market investment risk, won’t do much to help against inflation’s erosive effect. The investment tool most likely to help the investment portfolio keep pace with inflation is stocks – probably in the form of mutual funds as previously covered. Historically, stock investments have keep pace with or exceeded inflation’s negative impact.

However, a retiree cannot pay for groceries with shares of a mutual fund. Doing that will require shifting some portfolio shares to cash or put money in the bank. A way to approach this is to sell portfolio shares each year or so and put the money into an income account. Retirees can use this account to pay bills, buy food and other necessities, and generally, live. Meanwhile, the remaining portfolio will continue to grow and provide protection against inflation’s impact.

A conservative approach would be to hold about three year’s cash reserves in a bank or money market account. Then, as that account is reduced, shift money from the longer-term investment account into the income account. Doing this will remove some concern over market ups and downs because the income account will always hold enough funds to pay current expenses.

This approach is sometimes called a bucket system and may use two or more buckets, depending on the portfolio’s size and the individual’s needs and goals. It’s only one approach to staying financially well during the retirement period. Others may be worth trying to determine what will work best for each individual. As always, working with a trusted, competent advisor can be helpful when making these decisions.